Responding to Aggressive Behavior

Tips and Tricks to Maintain Your Sense of Control

Does this scenario sound familiar to you?

We gathered all the children on the carpet to read a story. Sam did not want to sit down. Instead, he went to the library area and began to climb on the furniture. I began to read the story and Sam started to shout, “Why don’t you shut up!” When I finished reading the story, I started to prep the tables for lunch. My co-teacher did movement games with the children on the carpet. Sam approached me and said, “I’m going to help.” I responded, “No, thank you. You may join the group.” Sam then tipped over two chairs before making his way over to the group. He then took out the container of bean bags and dumped them on the floor. Next, Sam threw the bean bags at the children. My co-teacher moved the children away from Sam. Sam began to throw the bean bags at me. Sam then picked up the wooden blocks and threw them across the room at the children.

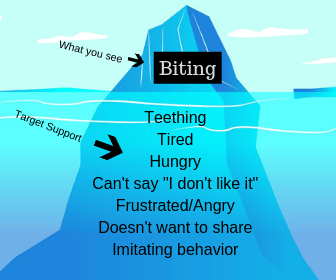

If it does, you are not alone. In my conversations with preschool teachers, I have frequently been told about similar experiences. Challenging behaviors are everywhere, and teachers are wondering, “How do I stop aggressive behavior when I can’t touch them?” In my previous post, “ 5 Step Process for Managing Challenging Behaviors ”, I listed a 5-step process for addressing challenging behaviors. However, the initial 2 steps – (1) Tracking behavior and (2) Identifying reasons for the behavior – can take a few weeks to complete. While this is happening, you are left dealing with a child who has repeated outbursts that may include throwing furniture, yelling and screaming, hitting, and pulling hair. In this article, I am going to give you tips and tricks for responding to these aggressive outbursts. However, these tips should be used alongside tracking behavior. Remember, the best way to manage challenging behaviors on a long-term basis is by identifying the “reason” behind the behavior and targeting your supports to address this reason. To learn more about this, check out our previous post here !

It is important for teachers to remember that it is not uncommon for young children who have not learned to manage their emotions to have outbursts and direct their frustration at a teacher. Children are not born knowing how to recognize and control the range of human emotions. This is something that is learned with the guidance and support of a caring adult. Many children who exhibit aggressive behaviors lack language, impulse control, or problem-solving abilities. Thus, they are unable to handle frustration in an appropriate way when they encounter situations like the one above. Minor outbursts, or tantrums, are developmentally normal for children ages 2 – 4, as they are learning to navigate a complex social world.

So, how do you respond when a child is throwing and yelling as in our above scenario? These are the strategies that have worked for me:

1. Stay Calm!

This is by far the hardest step, but the most important. How we respond to children’s outbursts and aggressive behaviors will affect whether it continues to occur or whether the child learns more appropriate ways to handle their emotions. Children who are explosive need calm, nurturing, and confident teachers, as they become models for the children of how to appropriately manage strong emotions. Repeatedly ignoring or getting angry with children who have outbursts can inhibit their brain development and the acquisition of necessary social skills. In fact, rejection, abandonment, and shame have been shown to make a child feel more rage and thus, increase the likelihood of more outbursts. Additionally, you have less chance of reaching a child when you shout at them.

I do two things to help calm myself in these situations. First, I use Becky Bailey’s S.T.A.R approach from Conscious Discipline. S.T.A.R. stands for Smile, Take a deep breathe, And, Relax. Using this approach ensures that my breathing and heart rate remain calm. I also use reframing thoughts to see the behavior from an objective perspective. Instead of thinking, “Oh here we go again” or “He’s trying to hurt me.” I think, “He’s really angry right now. He needs me to help him calm down.” By using both techniques, I ensure that I approach the situation positively and ready to help the child “learn”. This response sends a powerful message to my entire class.

2. Intervene to stop the dangerous behavior

It is your responsibility to keep all the children in your care

safe. Any dangerous behaviors require

your immediate attention. Remember,

ignoring these behaviors does not teach the child the needed social skills to

control his behaviors in the future.

In the scenario above, the teacher would approach Sam and get down on

his level. She would firmly say, “Stop

Sam. You may not hurt people.” Sam can be directed to a cozy corner or other

safe space in the classroom to calm down.

Sam is told, “I will keep you safe.

I will not let you hurt anyone or yourself. You can leave the safe place when you are

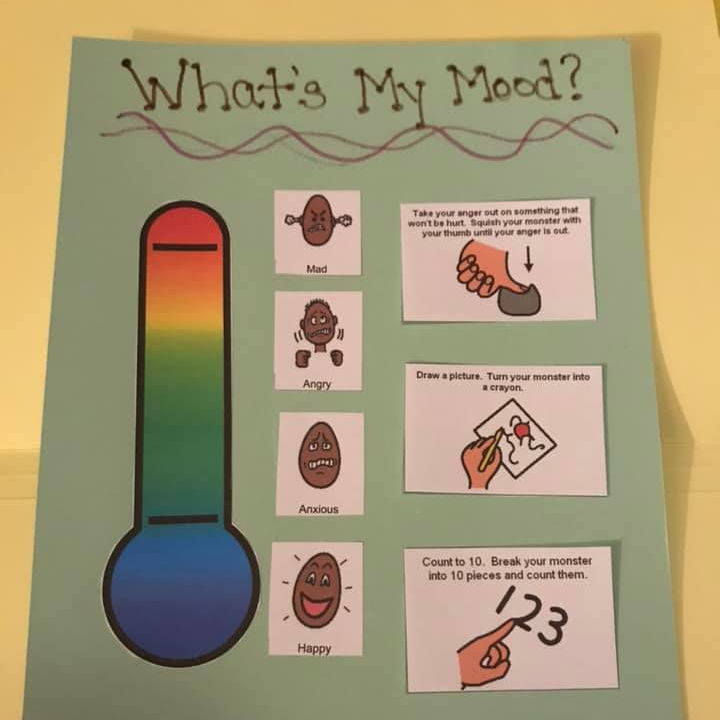

calm.” In my cozy area, I have a mood

thermometer and calm down activity choices for the child to choose from in

these moments.

When a child is in the middle of an outburst, you can not reason with them. This is not the time to discuss their behavior or how it hurts others. During this step, your focus is on getting the child calm. You may need assistance from administration or another teacher during these moments, as you’ll need someone to assist with the child having an outburst and someone to be with the other children. For children who have frequent aggressive outbursts, you should create a response plan so that everyone knows what to do in these situations. The response plan should be included in the Behavior Support Plan discussed here.

3. Acknowledge the child’s feelings and wishes

When children are having an uncontrollable outburst, it is frequently connected to strong emotions. By acknowledging how the child is feeling, you show the child that you understand them. A child who feels understood is more open to hearing what you have to say. In the above scenario, the teacher would acknowledge Sam’s initial wishes by saying, “You don’t want to listen to a story” or “It seems like you don’t want to sit for the story.” By acknowledging Sam’s feelings about story time, the teacher would have shown Sam that she understood how he felt. This would also allow the teacher to initiate a discussion with Sam about the different choices he has. For example, “Would you like to help me prep the tables for lunch (this is before his outburst) or would you like to put together a puzzle at the table.” This simple message goes a long way in communicating to young children, “I care about you” and “I am here to help you.”

4. State the limit clearly and say what behavior is acceptable

Limits on children’s behavior need to be communicated using simple terms that are specific and direct. Children also need to know what they can do instead. When a teacher states a limit, but does not offer an acceptable alternative, the child may continue to do the unwanted behavior because they do not know what else to do. Children rely on the adults in their environment to guide them in making positive choices. In the above scenario, the teacher would limit Sam’s yelling by saying “I don’t like it when you speak to me using hurtful words. Take a deep breathe. Use a calm voice and “nice” words so I can help you.” Sam could also be directed to use the cozy corner, or other calm down place, until he is ready to talk.

To make limits visual, I have created a “I can’t do/I can do” visual guide to show children behavior expectations and help them choose appropriate ways to express their frustration. Things that are on the “I can’t do side” include hitting, throwing toys, yelling, etc. (any behaviors that the child has done in the past). Things that are included on the “I can do side” are listening to music, reading a story, blowing bubbles, counting to ten, etc. This chart is introduced to the child when they are calm. It is then shown to the child when they are showing signs of becoming angry/frustrated. In this above scenario, the teacher would have shown Sam the chart when he started yelling. Once the child is in a full-blown outburst, the guidance from step two applies until they are calm. Once they are calm, the “I can do/I can’t do” chart can be used to discuss what happened and different ways the child could have responded.

5. Offer a final choice

There will be children who chose to test the limits of your guidance. These children will need your patience, as you continue to set firm limits for their behavior. In these moments, keep your message consistent. The child needs to know that their behavior must stop and you are committed to following through with your directions. In the scenario above, the teacher would give Sam a final warning by saying, “If you continue to throw blocks, you will have to leave this area. I will not let you hurt anyone.” If Sam continues to throw the blocks, the teacher will gently guide him to another area of the room that is safe and away from other children, preferably a cozy corner or calm down zone.

There may be times when a child’s unsafe behavior requires you to hold them. This is something you should discuss with the administration at your program. Knowing the limits of the touch policy at your program will help you know what the best response in these scenarios is. Holding some children helps them to calm because they may be overwhelmed by the emotions they are feeling and unable to calm themselves. Your touch becomes a sense of comfort that assists them in calming down.

The best approach to managing aggressive behavior is to prevent the outbursts by managing the child’s triggers. Knowing what sets a child off, allows you to set up your environment, routines, and interactions to minimize the effect of the triggers. If the teachers in the above scenario knows that Sam does not like group times or being in spaces with a lot of children, they would avoid his entire outburst by telling him story time was coming and offering him a choice before announcing it to the class. Additionally, the throwing of the blocks could have been avoided by allowing Sam to help prep the tables for lunch. This provided a great opportunity to assist Sam with calming down and talking with him about his previous yelling and teaching him other ways he could have handled the situation. It is also important to praise Sam’s positive choice, choosing to help set up for lunch, as opposed to continuing to distract from story time. By noticing and stating his positive choices, you encourage him to continue to make them and to know that he can get your attention in this way too!

Sign up for our newsletter to receive all the articles in our challenging behavior series in your inbox!

Looking forward to reading your comments below! What are challenging behaviors you are currently experiencing? How can these strategies help you maintain control in your classroom?

Do you have a process for addressing challenging behaviors in your early childhood program? Our live, instructor-led virtual training, Breaking the Behavior Code: Discovering the "Why" Behind Challenging Behaviors will teach you our 5-step process. Sessions running in September and October.