How to Conquer Social Conflicts in Preschool

A Proven 5-Step Conflict Mediation Process

Social conflicts are everywhere in a preschool classroom. Children fighting over a toy in the block area, telling other children, “You can’t come to my party”, and arguing over who gets to line up first are common conflicts every preschool teacher encounters at some time in their career. Let’s face it, preschool children simply are not good at solving social conflicts and need our guidance and support to handle these conflicts prosocially. It’s important for preschool teachers to remember that solving social problems is not just a struggle for young children, but adults as well. How often have you witnessed adults yelling and pointing fingers while driving, asking to be removed from a classroom because they don’t get along with a co-worker, or ending a long-time friendship after a disagreement over money. Learning how to manage social conflicts is important for children when going about their day in our preschool classrooms, and it is also an important life skill. One of the thrive skills discussed in this article.

I have often heard preschool teachers respond to these social conflicts by saying, “We are all friends!” If you think about it, this phrase is misleading. Are you friends with all your co-workers because you all work at the same job? Probably not. For us to expect all of the children in our classroom to be “friends” simply because they were placed in the same classroom is unrealistic. The definition of a friend is “a person who one knows and with whom one has a bond of mutual affection”. When you think about it, the children in your room are all classmates, and a few are friends. It is more appropriate to teach children to be kind to others, how to solve conflicts peacefully, and to respect the opinions and views of others. These are long-term life goals that will benefit the children in our care for their entire life.

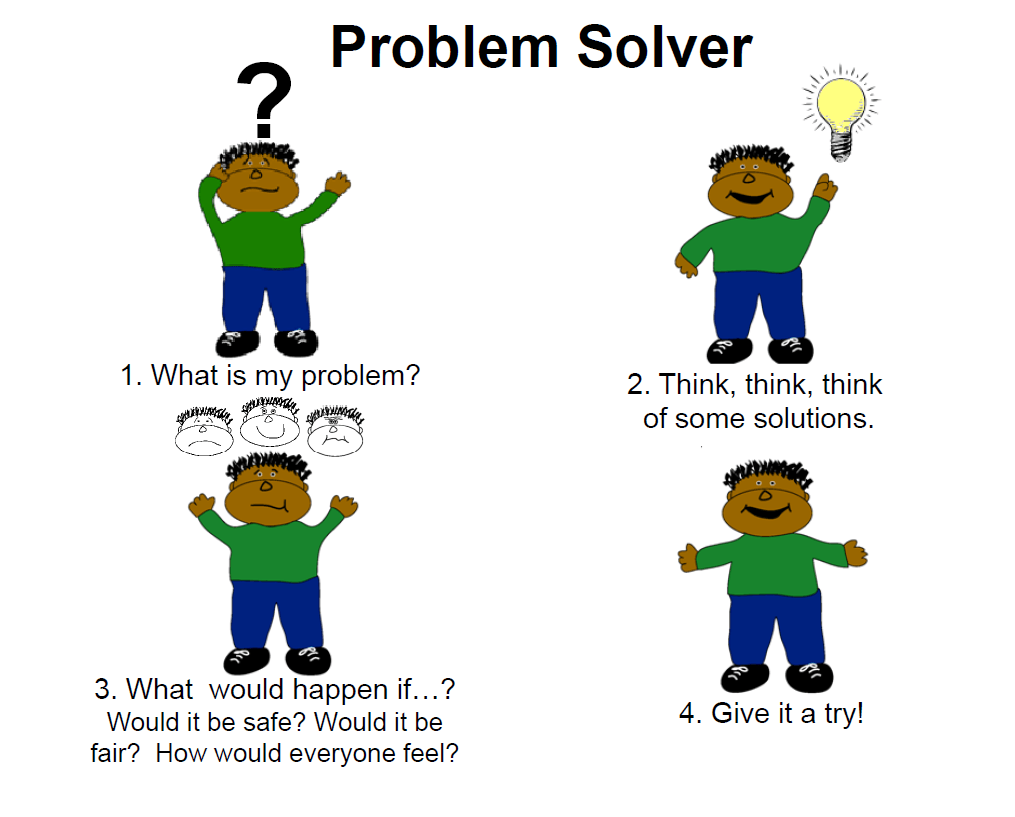

We know that preschool children learn best when they have the opportunity solve problems that are meaningful to them in everyday experiences. This means that the moments when children are engaged in conflicts present a unique “teachable moment”, where children get to see conflict mediation in action and practice using the steps to solve their own conflicts. Over time, children internalize the conflict mediation process as an effective response during conflict and begin to use the steps without adult assistance. This helps them better manage their emotions during conflicts and cope with social challenges calmly and productively.

It’s important for preschool teachers to continually observe for these “teachable moments” when children are having conflicts in their classroom and to help them think about ways to solve their own problems. The teacher’s role is to help the children identify when there are conflicts, find potential solutions, reach a consensus, and implement the agreed upon solution. In this approach, the teacher facilitates the problem-solving process by asking open-ended questions and allowing the children to generate their own solutions.

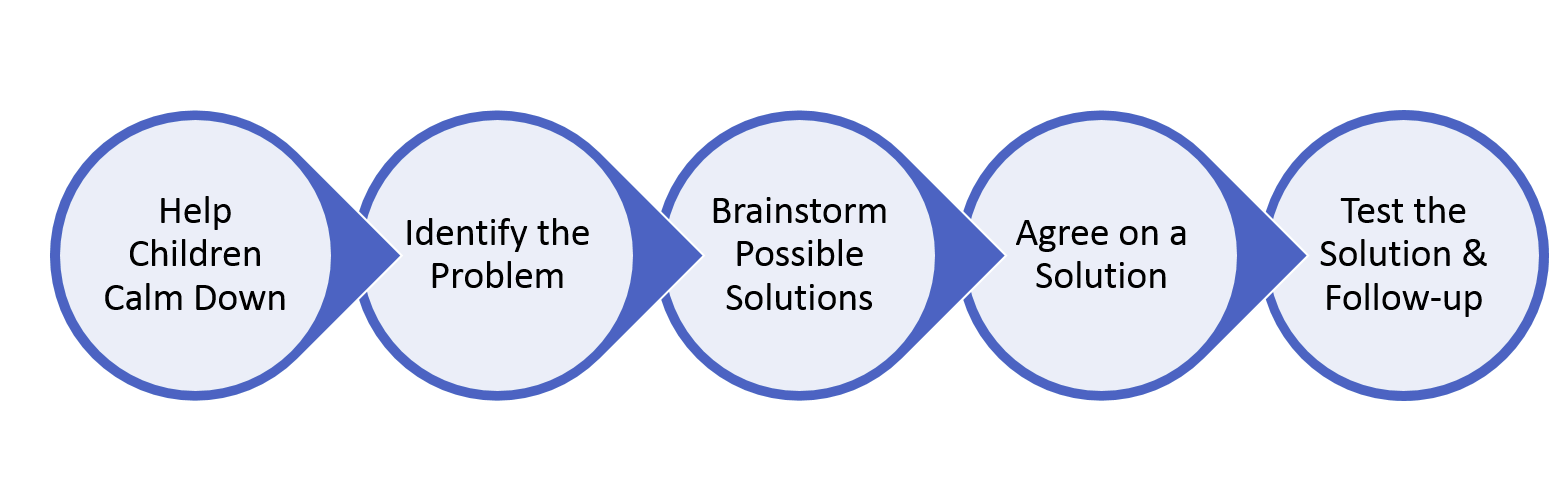

So, what are the 6-steps I use to mediate the conflicts between children in my classroom? Here they are:

Step 1: Help Children Calm Down

When children are upset, hitting, or fighting, the first step is to defuse the situation. Remember, young children typically fight about actions (things other children do) and things (toys, materials, activities). Teachers should try to settle conflicts before they escalate by immediately responding as soon as they hear voices rising. Most conflicts will calm when you move closer to the children in these moments. When hitting, biting, or other physical actions occur, the teacher should approach the children calmly and stop all hurtful actions by saying, “All hitting must stop. I know that you are angry, but it is not ok to hit.” The teacher would then get down on the children’s level, use a calm voice, and when appropriate gently touch the children to offer comfort. For more strategies on how to respond to aggressive behaviors, check out this article.

It’s important for teachers to acknowledge children’s feelings when deescalating the emotions of the children involved in the conflict. I state feelings concretely by saying, “You are feeling upset” or “You look sad”. I also show the children what they look like with my body postures and facial expressions. If children are using hurtful words toward each other, I will reframe these statements by saying, “You are feeling angry right now, it is not ok to call people names when you are angry.” If needed, I will offer a cooling off period where the children are separated before talking about what happened. I also tell children, “I need to hold this while we talk”, if they are arguing over a toy or other object. This will usually redirect their attention toward me, as opposed to continuing to fight over the object.

Step 2: Identify the Problem

Once everyone is calm, I will start asking "what" questions to gather information about what happened from the children. For example, I will say, “What happened” or “What is the problem?” It’s important to get each child’s perspective by offering a chance for each child to share their side of the story. I usually accomplish this by sitting everyone down and saying, “What happened? Johnny will tell me first and Nathan will listen. Then, Nathan will tell me what happened, and Johnny will listen.” This provides clear directions to the children about my expectations for talking and listening. It also shares with the children that everyone will get a chance to speak.

It is important for you to simply listen to whatever the children have to say without judgement during this step. This assures the children that it is safe to communicate what happened. If a child fears getting in trouble for what happened, the children may not share the complete story and the teacher will not be able to talk the children through the specifics of the problem. Remember, the teacher’s key role during this step is to LISTEN for the children’s perceptions of the problem so that they can repeat or restate relevant details for the children to consider.

After everyone has shared, I will restate back to the children what I heard them say from both children’s perspective. For example, I will say, “So, the problem is that Nathan was playing with a toy and Johnny took it from him. Johnny said he had the toy first and wanted it back.” This allows the children to add more details to the story, if needed, or clarify details that I may have confused. If the children share safety concerns, such as hitting, kicking, or pushing, I will explain limits at this point by saying, “It’s not safe to hit. Instead of hitting, let’s think of a safe way to solve this problem.”

Step 3: Brainstorm Possible Solutions

During this step, each child will share ideas on how to solve the problem. I simply ask, “What can we do to fix this problem?” As the children state their ideas, I will list all the possible solutions they generate on paper. Teachers should listen openly to each idea, as this models for the children how to listen to, appreciate, and consider the point being made by other children. Children consider what each solution will look like and what they think will happen if the solution is tried. I also ask the children, “How do you think Johnny will feel about this solution”, to help them begin to consider the other child’s perspective when problem solving.

For children who are not developmentally ready to provide ideas or those who do not have the language to communicate their ideas, the teacher would offer suggestions of ideas or assist the children with a language need with verbalizing their ideas. A great resource I use in my classroom is the Solutions Kit Cue Cards available here. These cards can be printed, laminated, and placed in a decorated shoe box for the children to pull solutions from when brainstorming ideas. The teacher would discuss with the children whether the solution could solve the problem.

Step 4: Agree on a Solution

After the children have created a list of possible solutions, the next step is to choose one solution to try together. The teacher reviews each solution on the list and engages with the children to find out which solution they think will be best. The goal during this step is for each child to feel that their input was considered and for the children – not the teacher – to decide on a solution that meets the needs of the group. This step can take some time, especially if one child is insistent on their suggestion being picked. It may take some teacher finesse and skill to merge two different solutions into one that works for everyone.

In this step, the solution picked is not as important as everyone agreeing to what the solution will be. When I have used these mediation steps with children in my class, they have chosen the “Eeeny, Minny, Miney, Mo” strategy at times. I knew the child who did not get selected would be upset and tried to guide them to consider what happens for the person not selected. However, if everyone agreed the “Eeeny, Minny, Miney, Mo” solution was the best one, I let them try the solution and comforted the child who was upset afterwards. The next time that strategy was proposed the child who was not selected did not agree to the solution. Trust that the children will learn which strategies work and which ones do not through their personal experiences with the outcomes of trying different solutions.

Step 5: Test Solution & Follow-up

During this step, the children try out their solution. The teacher will stay close by to monitor how the children are doing with the solution. If conflict breaks out or one child struggles with committing to the agreement, the teacher can talk with the children about how it is working and discuss if any of the other solutions on the list would have worked better. This discussion allows the child to compare what happened with what they expected to occur. Thus, the “teachable moment” becomes a “learning moment”.

If the solution is working for everyone, I usually acknowledge the fact that they solved the conflict by saying, “You solved the problem. Look at your solution. Everyone got a chance to throw the ball.”

Have you used these 5-steps to mediate social conflicts in your classroom? Share your successes, challenges, and adaptions below. Looking forward to reading your responses.

Do you have a process for addressing challenging behaviors in your early childhood program? Our live, instructor-led virtual training, Breaking the Behavior Code: Discovering the "Why" Behind Challenging Behaviors will teach you our 5-step process. Sessions running in September and October.