I have been a teacher my entire life. When I was growing up, I would put papers on my wall, place my stuffed animals in rows, have my little brother be the principle, bus driver… You name it! We would actually make my mom wait to drive as we pretended all of our “students” got on the “bus”. These memories make me smile, but they also remind me of what my vision of teaching was…….all my students happily going along with my plans, my routines, my activities. I never had a child who said, “NO!”, yelled, or ran away. They all wanted to be at school and LOVED it! Does this sound like what your vision of being a teacher was? Is this similar to what you expected? Could this be why so many of us feel that by providing for a child’s individual needs, we are in fact taking something away from the other children in the class?

How to Flip the Stories You Share about Challenging Behaviors

Could it be the "stories" we tell ourselves about children's behaviors?

I tell you this because we have expectations for the children in our care before we even meet them. Children’s abilities to meet our expectations often lead to us making assumptions about them. “He’s mean” when a child hits. “She’s defiant” when a child does not follow our directions. “She’s a good listener, a model student” for children who easily go along with our daily routines and activities. “I wish I had more children like her” to highlight the child we want versus the ones we have. The stories we tell ourselves about the children’s behaviors shape our interactions with them, views of them, and thoughts about our success or failure as a teacher. The stories we tell ourselves are POWERFUL because they become what we “see” and eventually “believe” about the child. Don’t believe me?

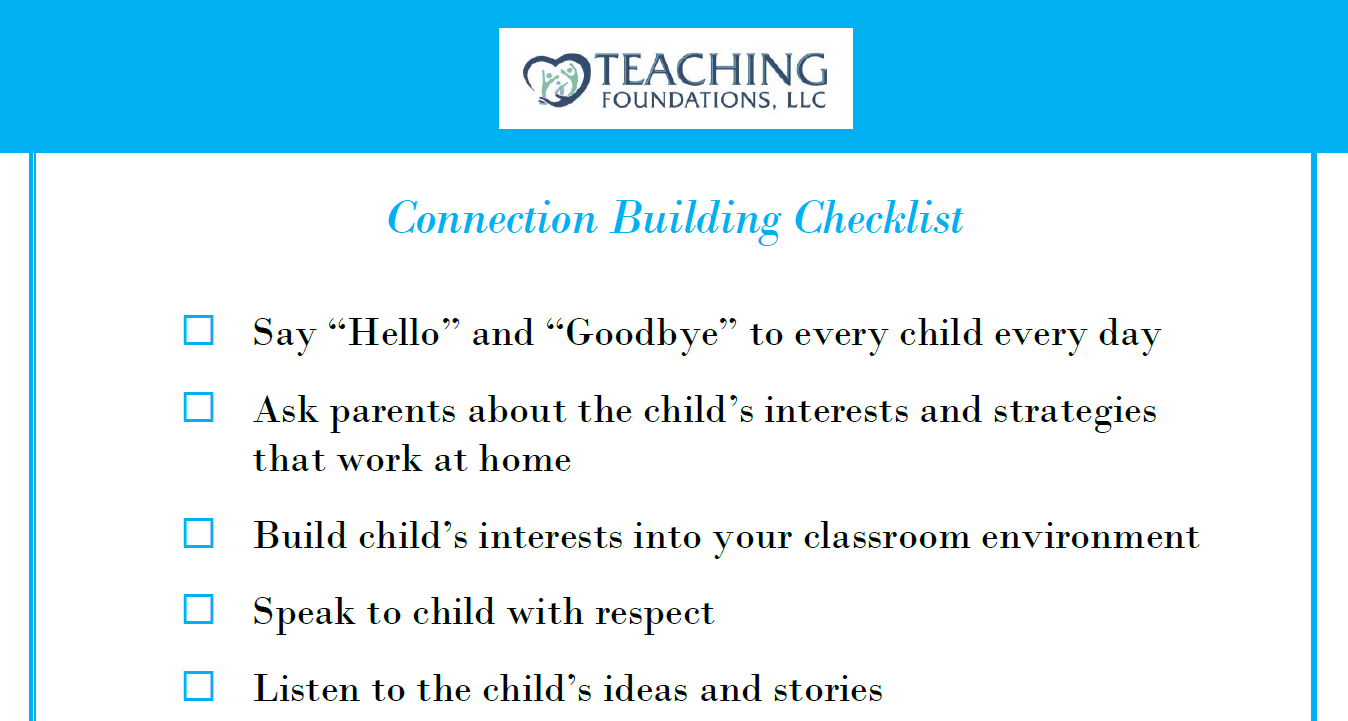

Play with the child when they are engaging in positive behaviors.

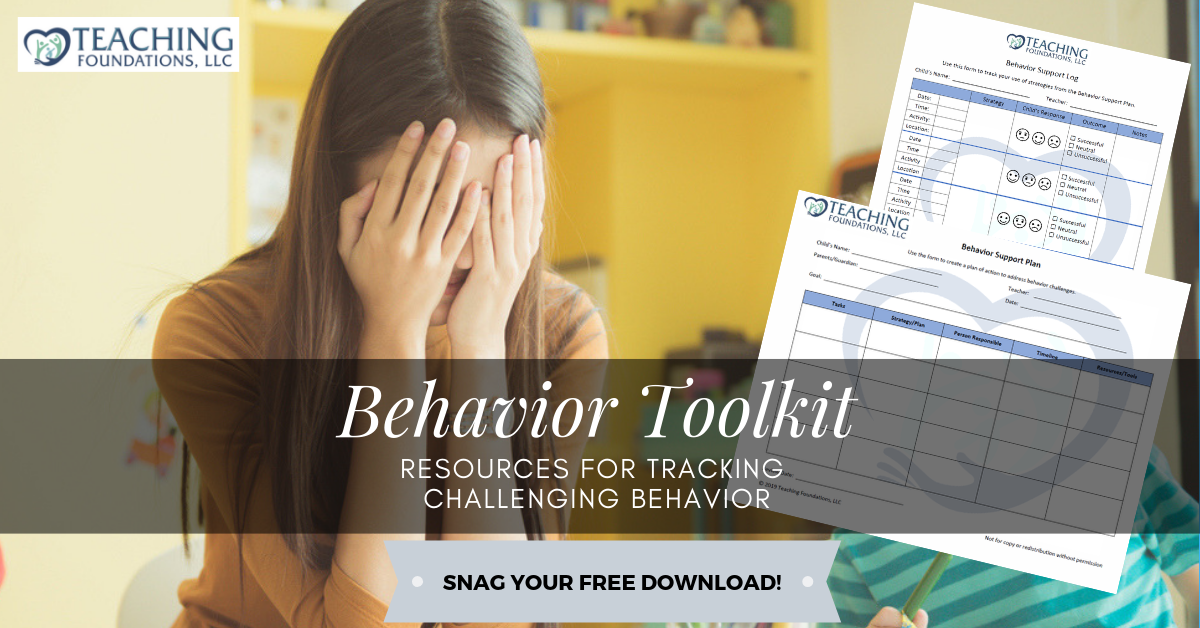

The thing I have noticed when working with

children with challenging behaviors is that we tend to “take a break” from the

child when they are not engaging in challenging behaviors.

Responding to the challenging behaviors requires so much attention and energy that when the child is cooperatively following routines, we use

that time to do the other things we don’t get to do while the challenging behavior

is present.

However, this “break” sends

an unintended message to the child:

"If you want my attention, engage in

challenging behaviors and I will come."

To break this cycle, I follow the 2 minutes for 10 consecutive days strategy to build a stronger relationship with the child with challenging behaviors. When the children is meeting expectations, I walk over and spend 2 minutes talking with them about what they are doing, listening to a story they have to tell, dancing to music, whatever. It is all about spending time with them doing something positive. You will learn a lot about the child as well, including interests, strengths, and what is happening at home. All of this is information you can use to help support them when they are struggling later. If anything, it helps you build the know, trust, and like factor into your relationship that is so vital to getting the child to want to follow your guidance.

Talk about the child's strengths more than their challenges.

Describe the child's behavior using objective language.

Use the word "can't" instead of "won't"

These are two small words with powerful meanings. Some people will say that the meanings of these two words are similar, but I challenge that they are not. In fact, the use of these words can directly impact how you respond to a child’s behavior because they have two very distinct meanings. “Won’t” means will not. This means that a child can do something, but chooses not to do it. For example, “Sarah won’t talk” means Sarah has the ability to talk, but is choosing not to talk at the moment. When you describe children’s behaviors be saying they won’t do something, you are telling yourself that they have the ability to do it, but are choosing not to do it. The child is being uncooperative, stubborn, or shall I say defiant.

However, children usually have challenging behaviors because there is a social or emotional skill that they have not yet learned. This means that they are not having tantrums because they won’t “control their emotions”, but because they can’t control their emotions. By saying they can’t, you are helping yourself to identify the child’s learning need. This simple change in wording starts the process of responding to challenging behaviors with a lens toward “teaching”.

Identify the missing social skills in the challenging behavior.

Do you have a process for addressing challenging behaviors in your early childhood program? Our live, instructor-led virtual training, Breaking the Behavior Code: Discovering the "Why" Behind Challenging Behaviors will teach you our 5-step process. Sessions running in September and October.